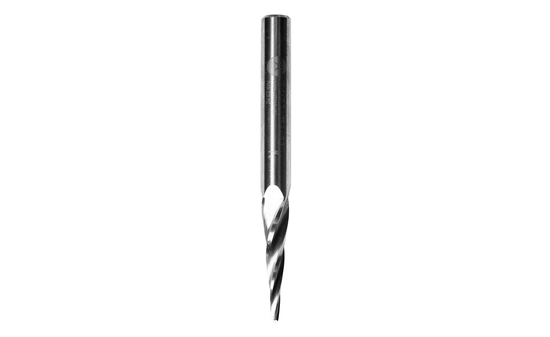

In principle, there are also special tools designed for different materials and cutting types. These differ both in the material (HSS, carbide, etc.) and in the cutting geometries.

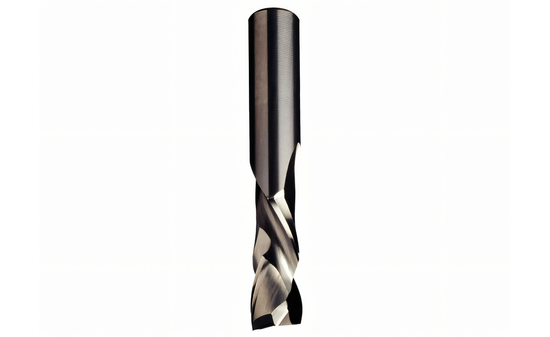

Roughing cutters, for example, have a rather aggressive cutting angle in order to remove a lot of material quickly without attaching great importance to the quality of the cut.

Finishing cutters remove little material and leave a clean cutting edge. Accordingly, flatter cutting angles are used here.

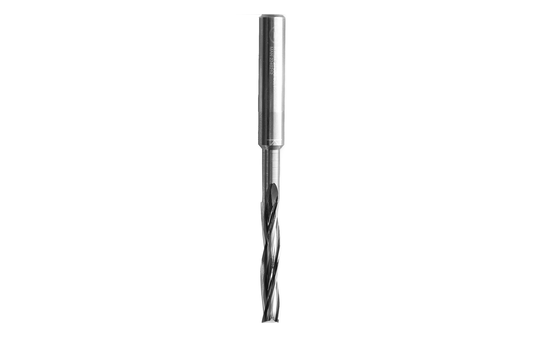

Routers with carbide cutting edges are suitable for wood and aluminium. These are either soldered to a steel shank (classic end mills for routers) or consist entirely of a carbide mixture. The number of cutting edges also plays a role in the tool life and the milling result. For aluminium, for example, single-edged cutters are often used to give the machine more time and to be able to remove the cut chips cleanly.